Turning The Screw

Kings Head Theatre • 14 Feb - 10 Mar

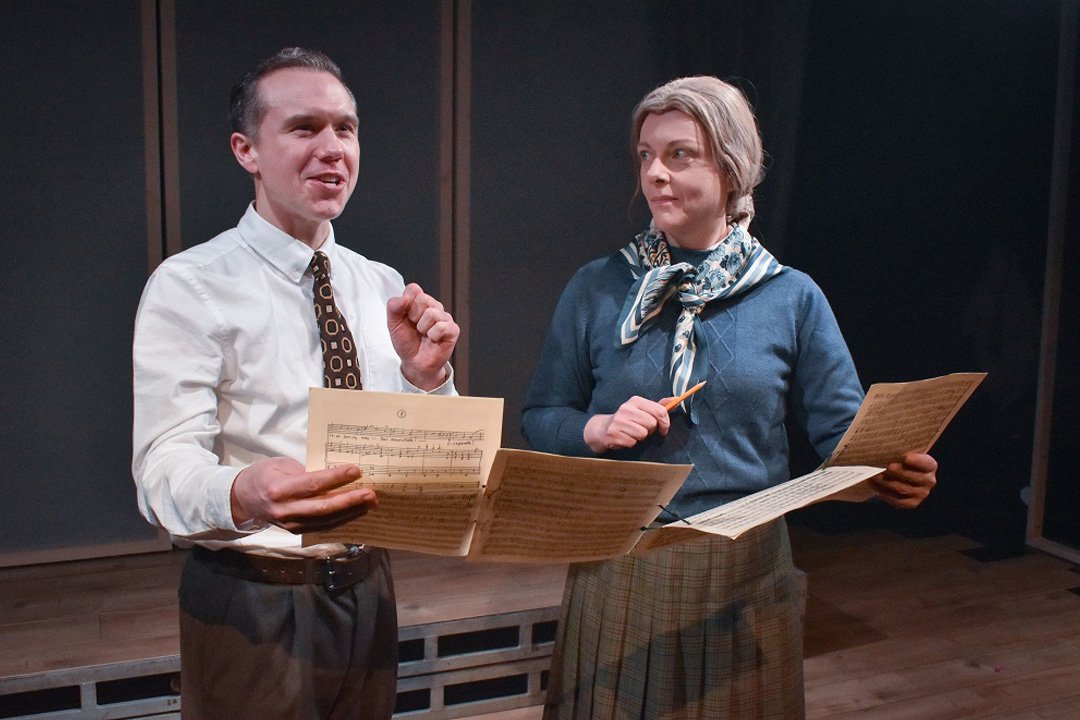

It was a welcome return to the Kings Head Theatre to watch Turning The Screw by Kevin Kelly, the theatre’s second main-stage offering at their new premises. Directed by Tim McArthur, this bio-drama is an interesting and often illuminating piece about the composer Benjamin Britten, (Gary Tushaw), but it’s not without its challenges.

Having widely been regarded as changing the face of British opera, and with his work still considered to be some of the finest to have come out of the UK since the 17th Century, Britten had the misfortune of living much of his life during a time when homosexuality was illegal. Despite this he managed to live with his partner of nearly forty years, Peter Pears, (Simon Willmont) who was himself an English tenor and appeared in more than ten of Britten’s opera’s. With recurring themes in Britten’s own work being those of an outsiders struggle against a hostile society, as well as the corruption of innocence, these same themes are mirrored both in Britten’s life and so, by default, here in Kelly’s play in which we bare witness to Britten’s rather less ‘artistic’ pursuits, namely his seemingly uncontrollable attraction to young boys, one of who is twelve year old David Hemmings (Liam Watson) who Britten has just cast to sing treble in his latest chamber opera, The Turn Of The Screw, (based on a Henry James novella).

It would seem the unbroken voice of the young boy was not necessarily the principal asset under consideration when Hemmings was being cast, but his shortcomings are overlooked in favour of his more attractive youth and ‘rough-around-the-edges’ charm. Recognising Britten’s habits of old, his director Basil Coleman, (Jonathan Clarkson) advises caution, and whilst, one by one, those closest too him, including his longtime partner, seem to echo this advice and warn Britten of the dangers he is inviting into his life… as well as into his home, Britten is seemingly unable to break the infatuation he has developed for his latest young protege.

Much like Gustav von Aschenbach in Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella Death In Venice, (on which Britten based his 1973 opera of the same name), Britten also tries to argue that this inappropriate attraction is in actual fact that of an artist who’s interest has only been sparked by the belief that he has discovered the physical embodiment of innocence, purity and angelic beauty. Whilst this is undermined in the play, and no doubt in Britten’s life, by the revelation that Hemmings is not the first boy in receipt of Britten’s dubious attention, for the Kings Head Theatre audience it is impossible to view Britten’s behaviour without considering the many scandals of more recent times that have involved high power figures and celebrities, all of who have abused their position, or status, in order to corrupt, or sexually manipulate minors. However, like Aschenbach’s own unrequited obsession, it would seem Britten’s feelings towards Hemmings were never acted upon, indicated at the start of Kelly’s play when a seemingly well adjusted and articulate young man takes to the stage revealing himself to be the adult Hemmings who, as he introduces the various characters that populate this period of Britten’s life, indicates, (as the real David Hemmings also did consistently), that Britten’s conduct was beyond reproach at all times. (NB: I had no idea whilst watching the play that this was the same David Hemmings who would go on to become the star of 1966’s cult classic film Blowup, and who had also directed David Bowie and Marlene Dietrich in 1978’s Just A Gigolo).

Despite Kelly’s script leaning towards Britten’s fixation for Hemmings as being a misguided but platonic one, (even if the sharing of a bed during a storm, and encouraging the minor to join him during a naked swim are themselves highly questionable actions), any sympathetic view we might have had towards this musical genius who, like every other gay man at the time was in fear of imprisonment if his sexuality was to be revealed, it is also Britten’s disregard for the emotions of those closest to him in order to further enable his questionable behaviour that reframes our perception of the man, despite Tushaw’s portrayal being fuelled by Britten’s more attractive passion for his craft and the sheer love of music. To further try and lessen the severity of our judgement about Britten’s intentions, there’s also an uncomfortable attempt to make Hemmings appear not such the juvenile innocent he might at first appear to be, but neither this, or the times Britten found himself living in, can excuse the inappropriateness of Britten’s behaviour, and it feels odd that Kelly’s play should really even try. This leaves some confusion over the ultimate takeaway from the play. Should genius’s be forgiven their indiscretions for the greater good of the art they create? It’s a stance that sits uneasily throughout this otherwise fascinating insight into Benjamin Britten’s life.

Tim McArthurs direction is solid throughout, and Laura Harling’s minimal set design leaves plenty of room for Vittorio Verta’s effective lighting to come into its own, (although two wooden frames beaded with a string of brightly visible LED’s took me slightly out of an otherwise convincing 1950’s atmosphere). A selection of musical interludes from various Britten productions also help bring the story to life. Liam Watson makes a good attempt to convincingly play the twelve year old Hemmings, but it ultimately becomes a bit of a stretch for the imagination, especially as we first see him as the adult Hemmings at the start of the play, and that disassociation only dilutes the impact that the age difference could have otherwise had, even if Hemmings age is repeated several times during the play lest we forget what Britten was prepared to sacrifice in order to satisfy his obsession. Professionally, Benjamin Britten became the first ever composer to be honoured with a life peerage, but whether this play makes you question the morality of the man’s personal life remains up for debate as Turning The Screw seems happy to present him as much as a persecuted and tormented gay man as much as it does a potentially predatory one.

★★★

review: Simon J. Webb

photographs: Polly Hancock